When not bemoaning the state of their love life, Elizabethan poets were wont to be worrying another sore tooth: the transience of our time on earth. Christina Rossetti's lines "To think that this meaningless thing was ever a rose,/Scentless, colorless, this!" go well with the following untitled poem, which was set to music by Orlando Gibbons.

Fair is the rose, yet fades with heat or cold.

Sweet are the violets, yet soon grow old.

The lily is white, yet in one day 'tis done.

White is the snow, yet melts against the sun.

So white, so sweet was my fair mistress' face,

Yet altered quite in one short hour's space.

So short-lived beauty a vain gloss doth borrow,

Breathing delight to-day, but none to-morrow.

Anonymous, in Norman Ault (editor), Elizabethan Lyrics (1949). The poem was first published in 1612 in Gibbons's Madrigals and Motets.

With autumn nearly upon us, this is apt:

Autumnus

When the leaves in autumn wither

With a tawny tanned face,

Warped and wrinkled up together,

The year's late beauty to disgrace;

There thy life's glass may'st thou find thee:

Green now, grey now, gone anon,

Leaving, worldling, of thine own

Neither fruit nor leaf behind thee.

Joshua Sylvester, in Norman Ault, Elizabethan Lyrics (1949). The poem was written prior to 1618, and was first published in 1621. "Worldling" (line 7) is a lovely word (both in the context of this poem and in general). It deserves wider currency, I think. It helps us to keep things in perspective.

Finally, here is a wider view of things.

To Time

Eternal Time, that wastest without waste,

That art and art not, diest, and livest still;

Most slow of all, and yet of greatest haste;

Both ill and good, and neither good nor ill:

How can I justly praise thee, or dispraise?

Dark are thy nights, but bright and clear thy days.

Both free and scarce, thou giv'st and tak'st again;

Thy womb that all doth breed, is tomb to all;

What so by thee hath life, by thee is slain;

From thee do all things rise, by thee they fall:

Constant, inconstant, moving, standing still;

Was, Is, Shall be, do thee both breed and kill.

I lose thee, while I seek to find thee out;

The farther off, the more I follow thee;

The faster hold, the greater cause of doubt;

Was, Is, I know; but Shall, I cannot see.

All things by thee are measured; thou, by none:

All are in thee; thou, in thyself alone.

"A. W.", in Norman Ault (editor), Elizabethan Lyrics (1949). The poem first appeared in 1602 in an anthology titled A Poetical Rhapsody, which was edited by Francis Davison. To my knowledge, the identity of "A. W." has never been discovered, although there has been much scholarly speculation as to who it may be. I've grown to like the fact that the writers of some of the best Elizabethan poems remain anonymous: it puts the focus on the poetry, where it ought to be.

Fair is the rose, yet fades with heat or cold.

Sweet are the violets, yet soon grow old.

The lily is white, yet in one day 'tis done.

White is the snow, yet melts against the sun.

So white, so sweet was my fair mistress' face,

Yet altered quite in one short hour's space.

So short-lived beauty a vain gloss doth borrow,

Breathing delight to-day, but none to-morrow.

Anonymous, in Norman Ault (editor), Elizabethan Lyrics (1949). The poem was first published in 1612 in Gibbons's Madrigals and Motets.

Kenneth Rowntree, "Old Toll Bar House, Ashopton" (1940)

With autumn nearly upon us, this is apt:

Autumnus

When the leaves in autumn wither

With a tawny tanned face,

Warped and wrinkled up together,

The year's late beauty to disgrace;

There thy life's glass may'st thou find thee:

Green now, grey now, gone anon,

Leaving, worldling, of thine own

Neither fruit nor leaf behind thee.

Joshua Sylvester, in Norman Ault, Elizabethan Lyrics (1949). The poem was written prior to 1618, and was first published in 1621. "Worldling" (line 7) is a lovely word (both in the context of this poem and in general). It deserves wider currency, I think. It helps us to keep things in perspective.

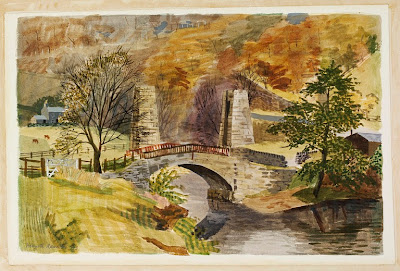

Kenneth Rowntree, "Bridge End Farm, Derwent Village" (1940)

Finally, here is a wider view of things.

To Time

Eternal Time, that wastest without waste,

That art and art not, diest, and livest still;

Most slow of all, and yet of greatest haste;

Both ill and good, and neither good nor ill:

How can I justly praise thee, or dispraise?

Dark are thy nights, but bright and clear thy days.

Both free and scarce, thou giv'st and tak'st again;

Thy womb that all doth breed, is tomb to all;

What so by thee hath life, by thee is slain;

From thee do all things rise, by thee they fall:

Constant, inconstant, moving, standing still;

Was, Is, Shall be, do thee both breed and kill.

I lose thee, while I seek to find thee out;

The farther off, the more I follow thee;

The faster hold, the greater cause of doubt;

Was, Is, I know; but Shall, I cannot see.

All things by thee are measured; thou, by none:

All are in thee; thou, in thyself alone.

"A. W.", in Norman Ault (editor), Elizabethan Lyrics (1949). The poem first appeared in 1602 in an anthology titled A Poetical Rhapsody, which was edited by Francis Davison. To my knowledge, the identity of "A. W." has never been discovered, although there has been much scholarly speculation as to who it may be. I've grown to like the fact that the writers of some of the best Elizabethan poems remain anonymous: it puts the focus on the poetry, where it ought to be.

Kenneth Rowntree, "Bridge to Cox's Farm, Ashopton" (1940)